On Insistence

Anyone can cook

Who is the third who walks always beside you?

When I count, there are only you and I together

But when I look ahead up the white road

There is always another one walking beside you

Gliding wrapt in a brown mantle, hooded

I do not know whether a man or a woman

— But who is that on the other side of you?

- T.S. Eliot, The Wasteland

RHYTHM OF THE WALL

Mountaineering is unforgiving. One cannot rhetoric one’s way out of a climbing accident. The altitude takes a toll on the body. The higher you go up, the thinner the oxygen is. The thinner the oxygen, the heavier the consequence of each decision becomes. And the heavier each decision becomes, the more decisions branch into the future. Often, the aim of mountaineering is seen as summiting, or reaching the summit. Yet this misses a crucial and larger point. The overall goal is survival; it is to live to reach another summit another day. If you’re dead, it’s hard to reach the summit. Then reaching the summit becomes half the battle. The objective is to come back to camp, alive. One of the first things you learn in mountaineering is having discipline around “turnaround time”. Knowing your ‘Turnaround time’ means that you know exactly how long it takes to the top and how long it takes to get back down to base camp. It also provides you with an exact time on when you have to turn back around regardless of conditions. If the weather looks bad, or if you run out of time -- you have to turn around. And try again another time. You have to honor your agreement with yourself to turn back. Most accidents and deaths on the mountain happen on the way down.

I have a recurring dream where I find myself climbing towards the summit. I’m relatively high up, probably that last push towards the summit. I’m climbing up the snow covered terrain with rocks peeking through. My breath is shallow, my boots are heavy, and my mind is numb and just as slow. In each dream, my starting condition is that I have already decided to take the summit in the bad weather, and it seems, fatefully, I have ignored my turnaround time. With each step, I can feel both the weight of my decision and this storm on my face. It seems to be getting worse. The sky is getting darker every time I check my watch. The wind has been blowing sideways for a while now, and the snow is piercing my face shard by shard. My crampons are frozen almost as much as my toes. The more I panic, the more oxygen I’ll lose, so I try to conserve my energy, but I am well aware I’m not in a great position with limited resources. I’ve been climbing for what feels like hours since base camp. When I check my map, I see I’m not far from the summit -- I think. I’ll keep going, I tell myself, one leg following the other in cadence. I know I am tired of fighting the elements and carrying my pack. I need rest. I can feel the frostbite worsening on my hands, and I tell myself this is a problem for a later time.

At one point, I’m climbing up a knife-edge arête leading to the summit. The ridge narrows to almost nothing, with steep drops on both sides. I look at it and the world dolly zooms and my gut slightly drops using whatever oxygen I just breathed in. The path, which angles steeply upwards, is incredibly exposed. The wind howls strong. I try to take it step by step up the ridge. The gusts are strong. Not stronger than before, but strong. I’m starting to look down on either side. It is as if I’m driving on the freeway, and suddenly realize the horror of how fast I am traveling in a metal box with other metal boxes similarly zooming around at unfathomably dangerous speeds. And as soon as I have that thought -- a gust of wind pulls me over the ridge and I tilt. Perhaps I’m tired enough or perhaps the wind isn’t any stronger, or perhaps I’m just tired at this point. Either way, I start crumbling down in a smoke of snow. I can feel my rope flying all over the place, zero orientation, my gear tumbling about. I also notice internally, a certain sense of calm. Internally, I find myself drifting towards a potential reprieve. But instead, I grab the side of the mountain. My hand is insistent. So is my arm, and soon the rest of my body stubbornly follows. Insistent on continuing.

I find myself holding onto a pickaxe. On the side of the mountain. Slightly dangling. Crampons still on, gear still largely intact. I take a deep breath. Inhale. Snow. Exhale. Snow. And here, I am reminded of Yvon Chouinard and the rhythm of the wall. He spoke about bivouac’ing on the side of the mountain, hanging from ropes, and camping in god-awful conditions. Trying to sleep on the wall itself. ‘You really get into the rhythm of the wall,‘ he said. Here I am, tethered to the side of a ridge with some rope that was made in a factory far far away. Gear that I’ve trusted and used over a period of time. A factory that produced millions of these tiny pieces of human-shaped metal, which is now the only thing keeping me hanging onto a massive piece of rock. A rock formation that emerged from massive tectonic movements of fire and rock hurtling and spewing volcanoes millions of years ago undergoing planetary-level shifts. And here I am, chasing the summit, only to end up being in the rhythm of the wall.

What is it about this quiet insistence? Where does it come from? What does it hold on to? I don’t know. I search for ways that allow me to let go; there are none. It does not seem to emerge from my responsibility. The hold comes from somewhere else entirely. A third person is holding on. I close my eyes. I hear the wind howling, and the snow flurrying. And I open them again. Yup, I’m the only one here. I slow, and I look up. For the first time, I see the color of indigo. A shifting opalescent spectrum of colors waving through the sky. I see it peeking through the storm clouds and the howling wind. Something bigger than you or I. My survival instinct is not my survival instinct. It is something more universal. An insistence that feels almost alien, as if I was answering the door to a gentle guest that knocks, only to let me know that I was already home.

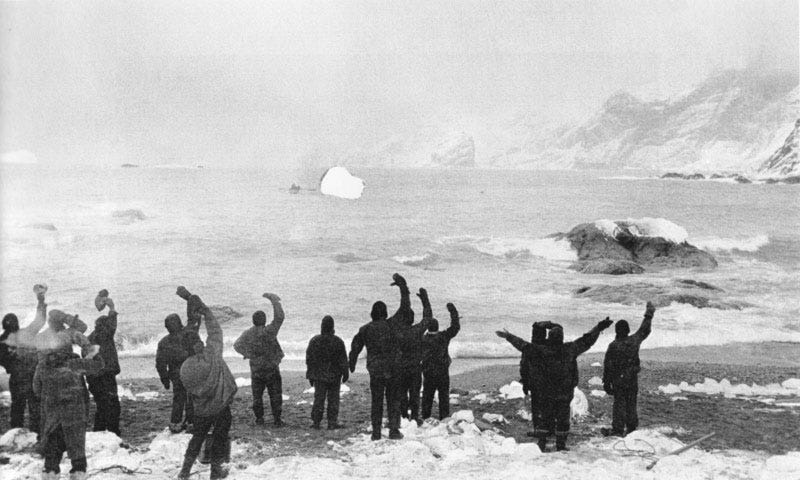

Is this the third man factor? Ernest Shackleton may be able to answer. He led the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1914-1917. A brutal expedition, the first land crossing of the Antarctic continent. An invitation that started with: “Men wanted for hazardous journey. Low wages, bitter cold, long hours of complete darkness. Safe return doubtful. Honour and recognition in the event of success.” And on this expedition, he and his men experienced the ‘third man factor’ a well documented phenomenon emergent in extreme situations. Shackleton wasn’t alone in this. Countless others have reported similar experiences. Krakauer describes them in “Into Thin Air”, a personal account on the 1996 Mt. Everest disaster, where climbers reported feeling or seeing presences beside them at the lowest of their lows on the brink of death. The phenomenon is consistent: extreme support and strength emerging equal to the strain of the situation. Shackleton described it as an incorporeal companion that joined him and his men during the final leg of his expedition when they were most stranded, most hopeless, most desperate on the pack ice for more than 10 months, when the expedition stretched beyond two years.

REMY & PAUL BOCUSE

Maybe asking what the third man factor is, is the wrong question. It reminds me of the Hawthorne Effect. The Hawthorne effect is based on an experiment to see if lighting would affect worker productivity. But it turned out that was the wrong question. The data was right, but the question was wrong. And perhaps we need a similar reframing here. The most interesting moment when working on a problem is when you have good data, or a good result, but your hypothesis is being framed incorrectly, and the data is nudging you towards a more interesting question. And so, with our discussion of the third man factor, perhaps the problem is not about what is the third man factor. It is: what does the third man factor pull out of us? In many ways it helps us overcome extreme situations that we would have never otherwise have made it in, but how? And where do we encounter it? Perhaps while documented heavily in expeditions and adventures, in what unexpected places do we find them? I’d argue we often find them in the act of making something that doesn’t yet exist. As that often requires pushing beyond to a place that lies beyond what you know you can already do. Because otherwise, how else would you have made it beyond that great unknown? And in those same moments, the same force emerges over and over to guide you and help you, the same way it helps climbers through the toughest moments on Everest. We have a harder time describing it because it’s not pack ice, or snow, or extreme and hostile conditions; visceral as a polar ice cap. Nor are its consequences immediate. While the danger is often not as obvious, it can still be just as dangerous.

I love Ratatouille, the movie. I loved it the first time I saw it. I’ve watched it many times over the years. If you’re not familiar with Ratatouille, it’s a story about Remy the Rat who’s obsessed with fine dining and cooking with impeccable taste who wants to become the best, and Linguini, a chef who can barely cut it in a kitchen. And somehow Remy guides and helps Linguini become an amazing chef. Anton Ego, the unrelenting critic, towards the end of the movie says as he eats Linguini’s dish: “in the past, I have made no secret of my disdain for Chef Gusteau’s famous motto, ‘anyone can cook’. But I realize only now do I truly understand what he meant. Not everyone can become a great artist, but a great artist can come from anywhere.” A children’s story is a pleasant manifestation of this idealization in a way that we are all willing to accept, both consciously and unconsciously. My interpretation of Ratatouille is that Remy the Rat is actually Linguini’s third man factor, not because he helps him, but because he pulls the great artist out of Linguini that was always already latent within him. Maybe the better way to say it is, a great artist can come from anywhere, but the core of that anywhere is often an extreme condition. Linguini simply couldn’t see himself under his imposter syndrome until he put himself in a grueling and extreme condition. Think of Remy as a part of Linguini’s that had to be activated through his forced extreme condition of working at a world class restaurant. He conjured up Remy, and in a way it helped him find the innate ability to cook the way he didn’t even know he could but always had imagined. This is what insistence demands of us under extreme conditions.

When I was a kid, I got obsessed with Paul Bocuse. When I went to his restaurant in Lyon, I sang a made-up song about Paul Bocuse. Then I proceeded to sing it over and over again until my parents completely and utterly regretted their decision. Linguini in some form reminds me of Paul Bocuse. For Paul Bocuse, his Remy, were those that came before him. Guiding him. It was Les Mères Lyonnaises, cooks like Eugénie Brazier1 (as she described it: « La vie peut s’arrêter à chaque seconde. Alors il faut travailler comme si on allait mourir à 100 ans et vivre comme si on devait mourir demain » ‘Life can end at any second. So you have to work as if you were going to die at 100 and live as if you were going to die tomorrow.) When Bocuse built l’Auberge du Pont du Collonges, it was a temple to these unseen spirits like Fernand Point at La Pyramide; they were his ‘Remy’ giving guidance through his toque blanche. In many ways making anything ultimately is an adventure, especially an entirely new cuisine that honors the past but presents the present as new again (Nouvelle Cuisine). Ultimately, for Paul Bocuse creating Nouvelle Cuisine was seemingly from his circumstances, something he couldn’t not do. Putting himself in that extreme condition where he would create something that didn’t exist before; elevating the status of a chef in ways previously unimaginable. To honour Nouvelle Cuisine is on thing, but it is a whole other thing to turn it into something new again if it doesn’t exist. Much like how Duke Kahanamoku had celebrated surfing and took it around with him sharing the joys with everyone around the world, Bocuse took fine dining with him as the cornerstone that would eventually making both French gastronomy and the chef profession itself synonymous with fine dining and a brand that it has become today around the world. It paved the way for all that came after him.

Remy is the appendage. Nothing is more apparent to the senses than the distinction between oneself and another being, like an animal and ourselves. It’s much easier to reason that we are following some guidance, or not even following a guidance, but we defer our decisions to actions made by some unknown force. The third man lives in extreme conditions, coming out to create only when not creating is the ultimate risk. The bigger the creation, the more potential for a bigger third man to emerge to help you, guide you on your path, on your journey, or your restaurant, or writing or art or whatever it may be. And the rhythm of the wall is the Stargate, the portal that summons the third man.

WIND, SAND & STARS

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s Wind, Sand and Stars is a book about aviation, but it’s really a book about survival. It’s a book about endurance, adventure, and about a time when aviation did not guarantee safety for every flight. A trans-Mediterranean flight felt like an adventure, exactly because it was. A time when flying a plane was less of a science, and more of art.

One of the most incredible experiences of this book is when he crashes in what he thinks is Libya with his flying partner. They have to figure out where they have crash landed, in which desert they are, and where the closest civilization is. Naturally, the survival mechanism and the feelings of going through the desert every day with no water kicks in. The thoughts that float through your mind day after day. The survival mechanism doesn’t really do justice to the variables that are constantly changing and harrowing. He ends up walking days and days through many of the unseen places that take the time to require something of himself all the way to the moment when he finally finds, after seven days, a passing Bedouin who helps him give water and helps him recover.

The book goes into detail of de Saint-Exupéry’s survival of the plane crash. Wandering in the desert. Seeing mirages over and over again, and being disappointed to the point that the expectation of disappointment precedes the discovery of mirages themselves. Especially in the later days of wandering the desert with no water. When his days accumulate, and the chances of survival narrows, and his experience of day and night and day and night of the desert start circling and blending into each other. Endless mirages preying on his mind, it eats into the surrounding container of his insistence, insistent on continuing. There is one striking section where he even admits that hope itself, over time, had become a luxury he could no longer afford to have. Not because he had no hope, but articulating the hope to himself, remembering its texture, its pleasures, had become too expensive of action for his mind and his well being. Imagine that. As if reminding yourself that everything is going to be okay is already too much work to think about because you are so low on morale and energy. But he insists on continuing with that bare survival mechanism alone, with the description of hope itself as something he can no longer carry. Hope’s name has been consciously forgotten, but unconsciously driven, by the third man -- pushing him from somewhere within himself.

And so in this recounting, in his memory of his experience in what exists in Wind, Sand, and Stars is a channeling of desire, or a lack of it. As de Saint-Exupéry recalls this experience and increasing destitution with a suspension of both future and past. He channels and as a writer writes about the memory of the story as one to be preserved, maybe for himself, maybe for others. His words are written to write the address and mail it to its recipient by inking the present. At the beginning of The Iliad, Homer invokes the Muse in Book I “Sing, O muse, of the rage of Achilles, son of Peleus, that brought countless ills upon the Achaeans.” Homer is asking the muse to tell the story. He is asking the goddess to remember the story through him (the orator) to channel the story of Achilles through him. As if this memory is larger than a single human’s memory recall. I think both Wind, Sand, and Stars and The Iliad share this desire to record or replay a consciousness existing beyond the memory of one person alone.

Writing becomes our personal submission of an experience into an ocean of universal voices. It is the universe recording and speaking itself into existence at the same time, as both artifact and invocation. Of course it’s easier to write about surviving crossing the desert after having made it across. As we know, by the very virtue of him writing the book, it’s self-evident that he survives. But he lived the tale separately from how he created the tale. And in a way, the creation of the tale itself is a different kind of act of defiance. There is a subtle but wide difference between living to tell the story and writing down the story itself.

It’s easy to see wandering in the desert. To read that storms and darkness can be turned into words. It’s not farfetched to forget that the author had to relive, had to work through, and cohere these words, to solidify that experience into words over and over again. And in this way, some of the best stories make the author invisible. As Ayrton Senna described driving F1 at his absolute peak: “And suddenly I realized that I was no longer driving the car consciously. I was driving it by a kind of instinct, only I was in a different dimension.” It is as if the story is conveyed to us so vividly, the experience so pure, the act of living it renders the author or the driver completely and utterly invisible. Not only invisible, but taken out of the equation, taken out of the scene itself. For him, the readers and the audience are the invisible ones.

And so, we must give credit where credit is due. It is true that de Saint-Exupéry encoded his unique experience into words that can be read again and again. And that act of not only remembering the very hardship he experienced exactly when he was at his lowest but also writing it transforms it from a solitary internal experience into a shared experience, a work of creation. Creation is a natural consequence of not being able to contain oneself, being moved by its meaning to the point of not having a choice but to write down those words and tell the story.

EPILOGUE

The gale force winds were still howling. The snow hit my face. And while I was dangling -- I heard it almost faintly at first, in the distance. I could faintly make it out, it was Beethoven’s Symphony No.9, ‘Ode to Joy’, the fourth and final movement 2. Yes, quietly at first, being on the side of this mountain, in the rhythm of the wall, I found myself at the lowest of my low, so it was hard to tell at first. I doubted myself. I’m just hearing things. Yet being on the side of the mountain, I heard it. And one by one, they came to me -- in droves. O Freunde, nicht diese Töne! Sondern laßt uns angenehmere anstimmen, und freudenvollere is what Beethoven added to Schiller’s poem himself. Insistence lives in the depths of these extreme conditions. Risk cuts the fluff and removes the comfortable every day stories we tell ourselves on a regular basis. I discovered what was already latent all along; slowly, voice by voice, step by step, rising together, hand in hand. Insistence was a chorus. And we were all singing, blaring symphony, crescendo and all; the entirety of my surroundings, humanity in unison.

Eugénie Brazier (1895~1977) was an incredible force of nature. Kicked out of her house for having a kid at 19, starting multiple restaurants and getting six Michelin stars in her life for many years, all while surviving Nazi occupation, and two world wars. Her chicken supplier joked that soon he would be expected to give the birds manicures before she would accept them. Literally the someone cooked here meme, because anyone can cook.

My favorite recording of Beethoven’s Symphony No.9, Op.125 IV. Finale is Herbert von Karajan’s Recording with Berlin Philharmonic from 1963. As common and popular as it has become over time it still continues to be a masterpiece. It never neatly fit into a classical music symphony movement, clocking it at around 25 minutes total which is uncommon. Even Beethoven had difficulty describing the finale to publishers himself as to what it actually was. It did not cleanly fit into any genre. At the time, there were some detractors like Verdi (more classical opera) but generally it was accepted and celebrated. Many successive composers like Brahms, Bartók, Dvořák, Bruckner, all paid homages to it in their own ways.

I feel refreshed having it read it. You are a good storyteller. Vividly did I traverse the gamut of vistae and spaces.